On a quiet morning in Lübeck, Germany, on March 6, 1981, a woman named Marianne Bachmeier walked into a courtroom with a calm but determined demeanor. What happened next would shock a nation and echo across the world for decades. Marianne, carrying a small loaded pistol in her handbag, took aim at Klaus Grabowski—the man accused of kidnapping, abusing, and murdering her seven-year-old daughter, Anna. In a matter of seconds, she fired seven shots into him, ending his life on the courtroom floor.

Her arrest was immediate, but Marianne showed no remorse. She had done what many parents might secretly dream of in their most broken moments: she exacted her own justice. Her act, raw and emotional, sparked global debate. Four decades later, Marianne Bachmeier’s name still resonates as a symbol of vengeance, grief, and the moral gray area between justice and vigilantism.

Marianne’s story began in hardship. Her childhood was marked by tragedy, trauma, and deep emotional wounds. Her father had served in the Waffen-SS during Nazi Germany’s reign, a shadow that loomed over the family. As a young girl, Marianne endured abuse and trauma. She became pregnant at sixteen and gave her baby up for adoption. Two years later, she became pregnant again and made the same heartbreaking decision. But in 1973, when she gave birth to her daughter Anna, everything changed. This time, Marianne kept the child and raised her as a single mother.

By all accounts, Anna was a bright, open-hearted little girl, full of curiosity and energy. She lived with her mother in Lübeck, where Marianne worked hard to make ends meet by running a small pub. Life was far from easy, but the two shared a deep bond. That bond was brutally severed on May 5, 1980, when Anna disappeared after a minor argument at home. She had decided to skip school and head to a friend’s house but never made it. On her way, she was lured and abducted by 35-year-old Klaus Grabowski, a convicted sex offender who had previously molested two young girls.

Grabowski, who lived nearby, had a history of violence and manipulation. While serving a sentence for his past crimes, he had voluntarily undergone chemical castration. But in an attempt to resume a “normal” life, he later received hormone therapy to reverse the effects. At the time of Anna’s murder, he was living with his fiancée and had returned to the community with little fanfare, despite his history. He held Anna captive in his apartment for several hours, during which time he abused and ultimately strangled her to death.

He placed Anna’s small body in a cardboard box and left it by a canal. Later that day, Grabowski returned to move and bury her, but his fiancée, who had learned of the crime, tipped off the police. He was arrested the same night at a local bar.

Grabowski’s arrest brought little comfort to Marianne. During his trial, he made disturbing claims, including an assertion that Anna had tried to seduce and blackmail him—an outrageous statement that only deepened Marianne’s anguish. Already struggling with the pain of losing her daughter, she now had to endure listening to her child being slandered in court.

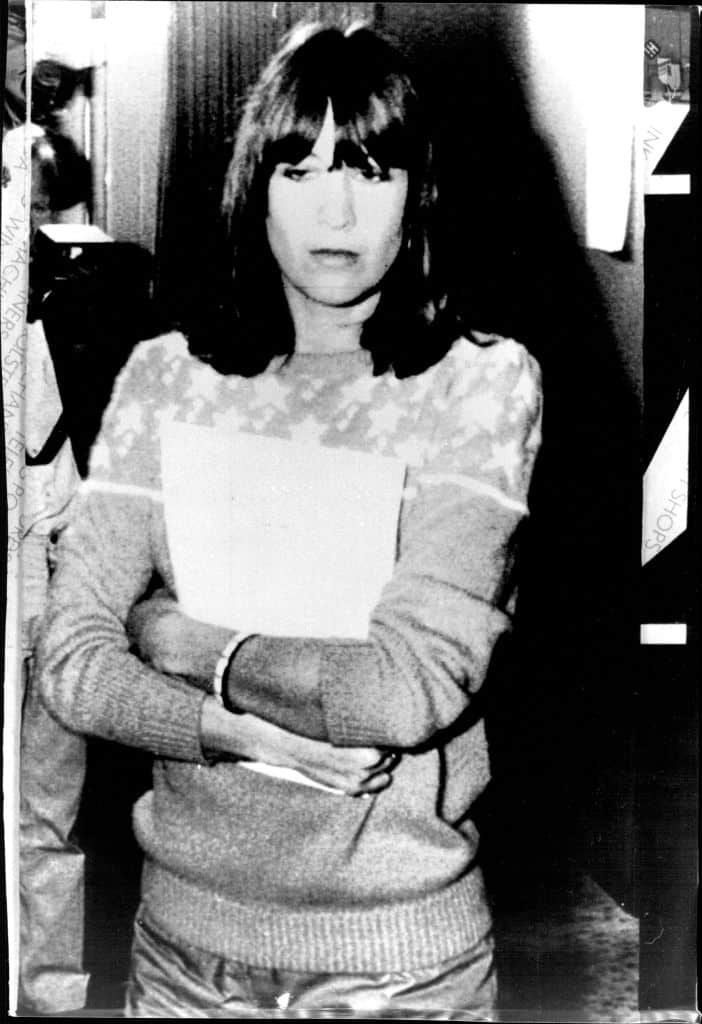

That morning in March 1981, on the third day of the trial, Marianne walked into the courtroom with a pistol hidden in her handbag. As the trial proceedings were about to begin, she stood up, pulled out the gun, and fired seven times at Grabowski. He died instantly. Her words were clear and cutting: “He killed my daughter… I wanted to shoot him in the face, but I shot him in the back … I hope he’s dead.” Witnesses, including police officers, recalled her calling him a “pig” moments after the shots rang out.

Her arrest was swift. Initially charged with murder, Marianne stood trial the following year. She claimed that she had acted in a trance-like state, driven by visions of her daughter in the courtroom. But investigators found evidence suggesting otherwise. Her familiarity with the firearm and the precision of her actions suggested that the act had been premeditated. In a handwriting sample she submitted during a psychological evaluation, she wrote, “I did it for you, Anna,” accompanied by seven hearts—one for each year of her daughter’s life.

The trial became a media sensation. Many Germans saw her as a tragic hero, a mother pushed beyond her breaking point. Others were more critical, insisting that justice must be left to the courts, no matter the crime. The press, initially sympathetic, began to dig into her past—highlighting her troubled youth, her time spent at the bar, and the children she had given up. Public opinion became divided.

Ultimately, Marianne was convicted of premeditated manslaughter and illegal possession of a firearm. She was sentenced to six years in prison, though she was released after just three. A national survey revealed just how conflicted the public was about her punishment: roughly one-third thought the sentence was fair, another third thought it was too harsh, and the rest felt it was too lenient.

After serving her sentence, Marianne left Germany, seeking a quieter life away from the spotlight. She moved to Nigeria, married a German teacher, and later relocated to Sicily after their divorce. In the 1990s, she returned to Lübeck after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Though she had tried to distance herself from her past, her name never disappeared from the headlines.

Even years later, interviews with Marianne revealed a woman still haunted by what had happened. In a 1994 radio interview, she spoke about the difference between her crime and that of Grabowski. She described in vivid terms the horror of her daughter’s death and her belief that Grabowski’s actions stripped him of any right to live. In another televised interview, she admitted that the shooting was deliberate, a calculated move to prevent Grabowski from continuing to lie about Anna.

Marianne died on September 17, 1996, in her hometown of Lübeck. She was buried beside her daughter in the same cemetery, their graves forever side by side—a visual reminder of a tragedy that reshaped a nation’s sense of justice.

Even now, her story raises profound questions. Was Marianne Bachmeier a mother driven to madness by grief, or was she a symbol of a flawed justice system that failed to protect the innocent? Her story still divides opinion in Germany and beyond, with some viewing her as a martyr and others as a vigilante.

What cannot be debated is the depth of pain she carried and the lengths to which a grieving parent might go in search of justice. Whether one agrees with her actions or not, Marianne’s story continues to stir reflection on justice, trauma, and the fragile boundaries between right and wrong.