Just weeks into his papacy, Pope Leo XIV — formerly Robert Prevost — finds himself under a cloud of controversy that threatens to cast a long shadow over his reign.

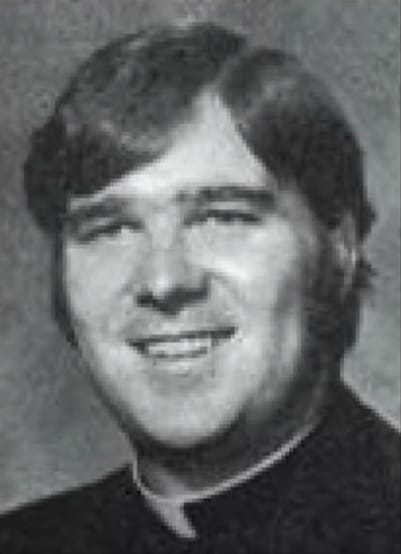

At the heart of the allegations is a now-defrocked Chicago-area priest, James M. Ray, who claims that Prevost knowingly approved his residence at an Augustinian monastery located mere steps from an elementary school, despite the priest being under restrictions following multiple allegations of child sexual abuse.

“I lived less than a block away from St. Thomas the Apostle Elementary,” Ray said, referring to the Hyde Park friary where he stayed from 2000 to 2002. “And he’s the one who gave me permission to stay there.”

Ray, who has been accused of abusing at least 13 children, maintains that then-Midwest Augustinian head Robert Prevost signed off on the arrangement. At the time, Ray had already been removed from public ministry and was under watch due to the severity of the allegations against him.

According to Ray, the friary — St. John Stone — was chosen because it was one of the few places willing to house him after the Archdiocese of Chicago sought accommodations for the disgraced priest. Church records later claimed that no schools were nearby, but St. Thomas was just around the corner, and a child care center sat directly across the alley. Neither facility was informed of Ray’s presence.

Ray is unapologetic in recalling the arrangement. “The Augustinians were the only ones who responded,” he said, suggesting the order was not pressured but willingly agreed to the placement.

A key piece of evidence is a 2000 internal memo reportedly circulated within the Archdiocese, suggesting that Prevost was aware of the details. Whether or not he was legally obligated to notify neighbors or school officials, critics argue that the moral responsibility was clear — and unmet.

A lawyer for the Augustinian order claims Prevost merely accepted Ray as “a guest of the house” and that oversight was delegated to the friary’s former superior, Rev. James Thompson, now deceased. Prevost himself has not publicly commented on the allegations.

Ray’s presence in Hyde Park came to an end in 2002, the same year the Boston Globe’s landmark investigation into clergy sexual abuse rocked the Catholic Church. He was officially defrocked in 2012.

Now 2025, and with Prevost elevated to the papacy, this decades-old chapter is resurfacing with renewed urgency. It’s not just the circumstances of Ray’s housing — it’s the broader question of how much Prevost knew, and how deeply he may have been involved in a decision that put a credibly accused abuser within arm’s reach of children.

Though Pope Leo XIV has never been accused of abuse himself, his new role as the global face of Catholicism makes past decisions all the more consequential. During his time overseeing bishop appointments at the Vatican, Prevost had publicly emphasized the need for transparency and proper formation for Church leaders. “Silence is not the solution,” he told Vatican News in 2023. “We must accompany and assist the victims, because otherwise their wounds will never heal.”

Ray, for his part, expressed a mixture of cynicism and amusement upon hearing Prevost was elected pope. “Why did it have to be an Augustinian?” he quipped, adding that the choice still gave off “very positive vibes.”

But that light-hearted remark comes in contrast to a deeper truth: Ray hints that he wasn’t the only problematic figure from that era — suggesting others remain shielded by the institution.

For a Church attempting to reconcile with its past, this latest controversy surrounding Pope Leo XIV is a stark reminder that old wounds do not simply disappear — and the call for accountability continues to echo in pews around the world.