The more I look back at the 1972 Oscars, the more it feels like a snapshot of Hollywood at a crossroads—old-school glamour still intact, but with bolder, rougher storytelling already taking over the industry’s center of gravity. It wasn’t just an awards night; it was a mood, a cultural flashbulb moment, and a reminder that the ceremony once had a kind of unforced electricity that’s harder to find today.

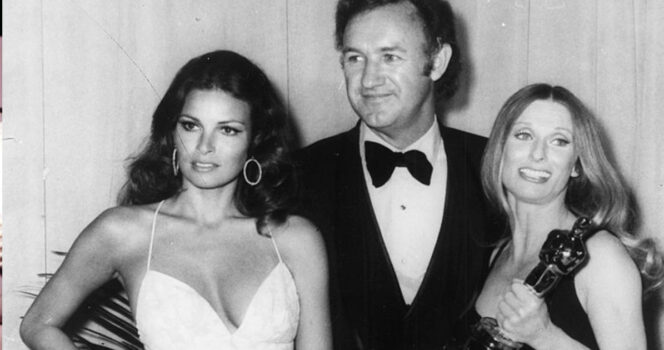

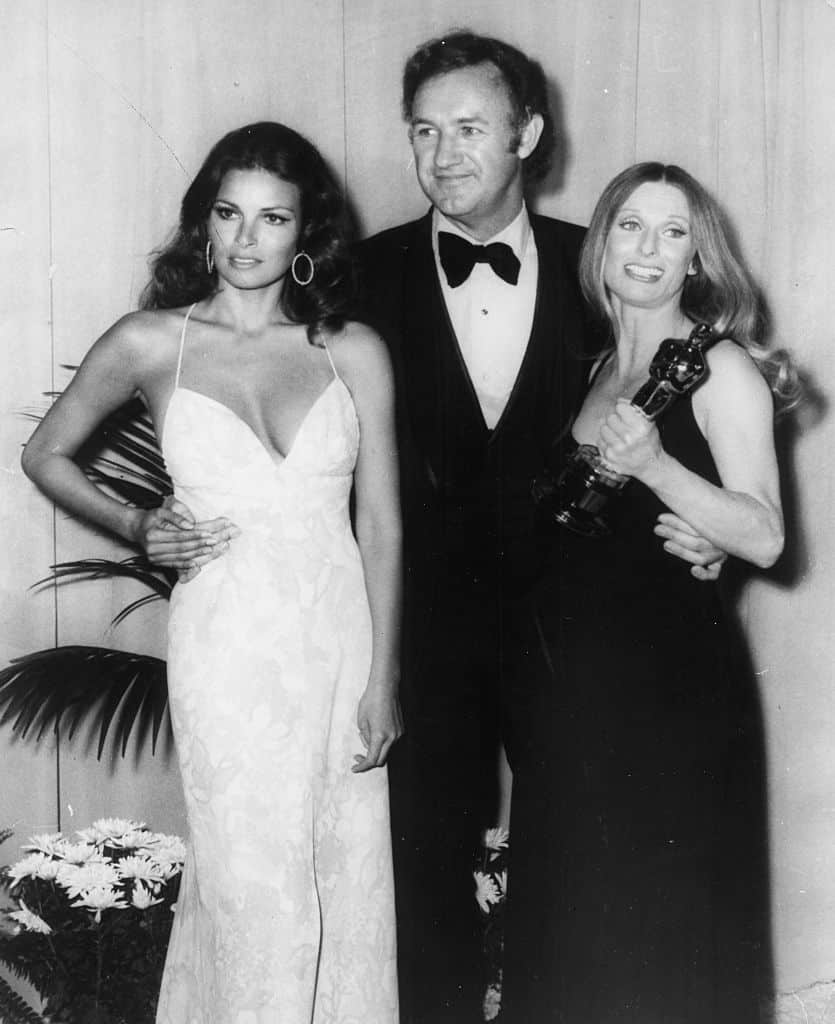

The 44th Academy Awards (held at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles) crowned The French Connection as Best Picture, and that choice alone says a lot about the era’s appetite. The film’s grit, street-level realism, and relentless momentum made it feel like a new template for thrillers—less polished fantasy, more lived-in intensity. It went home with five Oscars, including Best Director for William Friedkin and Best Actor for Gene Hackman.

Hackman’s win is still one of those “you had to be there” pieces of Oscar history, partly because he didn’t present himself as a glossy movie star playing dress-up. He came across like a working actor who’d been dragged into the spotlight by the sheer force of a performance. And he later described the experience of making the film with the kind of honest exhaustion that fits the movie’s tone:

”The film was totally different than anything I’d ever done. I’d never shot that much outside, and especially in the wintertime and especially in those conditions where we were just at it all the time. And I don’t think I’d ever been pushed as much by a director either, which was really good for me,” Gene Hackman said.

What’s also striking about that year is how the nominees collectively hinted at a changing definition of “important cinema.” You had A Clockwork Orange in the mix—provocative, polarizing, and undeniably influential—and Fiddler on the Roof reminding everyone that the big emotional sweep of a musical could still hold the room.

Meanwhile, The Last Picture Show landed like a quiet gut punch, and its awards for Cloris Leachman and Ben Johnson felt like a nod toward character-driven storytelling that didn’t need spectacle to leave a bruise.

Wikipedia

Outside the venue, the era’s tensions were right there, too. The ceremony didn’t exist in a vacuum—fans gathered, but protests did as well, including demonstrations aimed at Dirty Harry (despite it not being nominated), with signs reported in coverage from the time. It’s the kind of detail that makes the night feel less like a sealed-off celebrity pageant and more like an event happening in a real, messy world.

Then there’s the music—because 1972 didn’t just announce winners, it staged moments. Isaac Hayes won Best Original Song for “Theme from Shaft,” a milestone win that carried weight beyond the category itself.

In a modern broadcast, the music segments can feel like well-lit intermissions; in that era, the performances could feel like the show was briefly becoming something else entirely.

And if you want the emotional peak of the night, it’s hard to beat Charlie Chaplin’s return. After years of exile and controversy, he appeared to accept an honorary award and received what’s often cited as the longest standing ovation in Oscar history—about 12 minutes.

Whatever someone thinks of the Academy as an institution, that moment is difficult to watch without feeling the room’s collective recognition of legacy, loss, and the strange power of public forgiveness. His brief remarks hit precisely because they weren’t polished into a perfect speech:

”Oh, thank you so much. This is an emotional moment for me. And words are so feeble and futile. Thank you for the honor of inviting me here. You are wonderful, sweet people,” the English comic actor said.

To me, that’s why 1972 stands out: it blended craft and celebrity, nostalgia and rebellion, spectacle and sincerity—without looking like it was trying too hard. It celebrated the giants of an older Hollywood while handing the microphone to a newer kind of film language at the same time.

And maybe that’s the real difference people sense when they call modern ceremonies “bland.” It’s not that today lacks talent. It’s that nights like 1972 had the feeling of an industry changing in real time—captured in applause, in controversy, in bold winners, and in a few moments that still echo decades later.