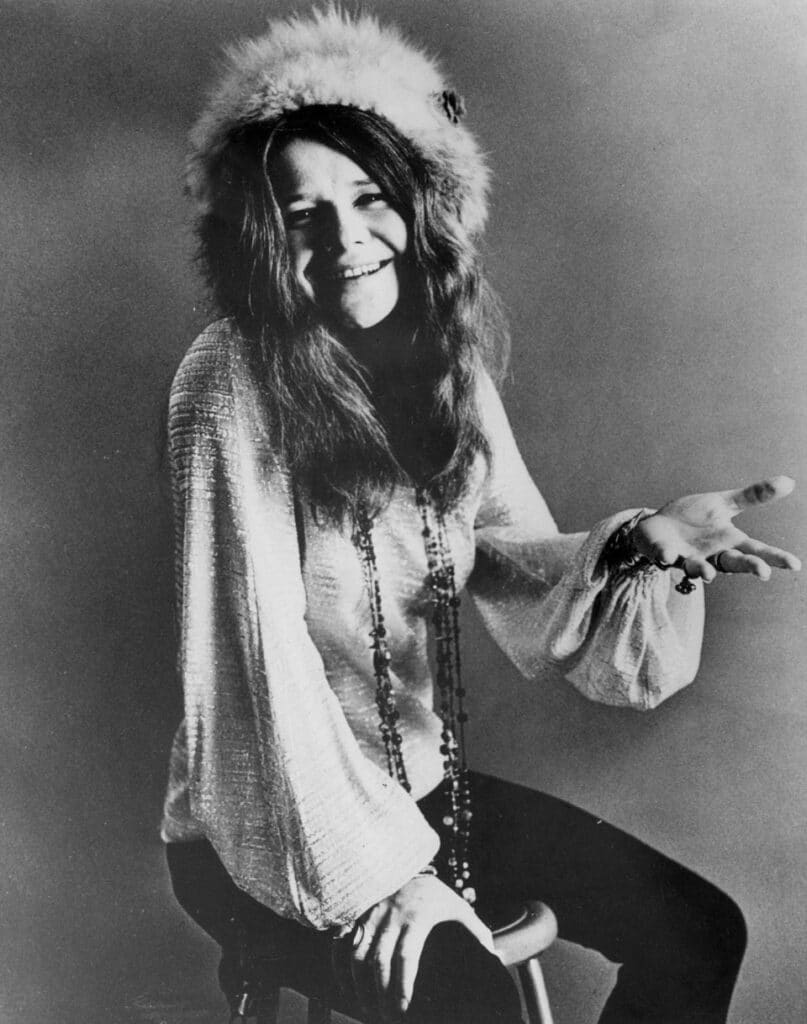

People used to say she was ugly.

For many who truly knew her, that idea never made sense.

She was slim, striking in her own way, with thick hair, soulful eyes, and a voice that sounded like it had been pulled straight from somewhere beyond this world. She rarely needed makeup. When she sang, it felt like something ancient and holy breaking loose.

The woman behind that voice was Janis Joplin—and her journey to becoming a legend began far from glamour.

She was born on January 19, 1943, in Port Arthur, Texas, to Dorothy and Seth Joplin, a deeply religious, working-class couple. Her mother worked at a local college, and her father was an engineer for Texaco. They hoped for a quiet, respectable life centered on faith and tradition.

But Janis was different from the start.

Growing up in a deeply segregated town during the era of Brown v. Board of Education, she gravitated toward ideas and people that set her apart. She devoured beat poetry, immersed herself in jazz and blues, and questioned the rigid social order around her. Alongside a small group of like-minded friends, she stood out as an intellectual liberal in a conservative environment.

By her teens, she had become Port Arthur’s first female beatnik. She frizzed her hair by drying it in the oven, skipped wearing a bra, laughed loudly, and openly rejected expectations placed on young women. She also discovered her love for blues and folk music—genres that spoke to pain, longing, and defiance.

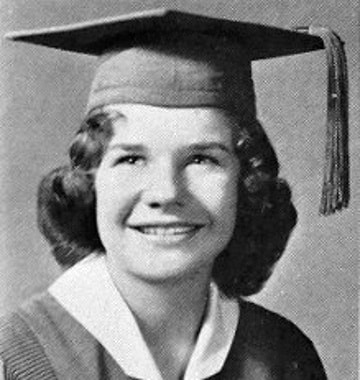

Those years were not kind to her. Janis endured relentless bullying, social isolation, and cruel judgments about her appearance. Severe acne left lasting scars on her face, deeply affecting her self-esteem. Classmates later recalled how quickly she went from being considered “cute” to being labeled “ugly.” Even her younger sister, Laura, described her skin as painfully inflamed and constant.

The criticism followed her into college. After briefly attending a local school, Janis transferred to the University of Texas at Austin. She walked barefoot across campus, wore Levi’s to class, and carried her autoharp everywhere, ready to sing whenever inspiration struck. She lived for ideas, books, and music—but remained painfully aware that she didn’t fit in.

In 1962, she was nearly voted “the ugliest man on campus” in a humiliating student contest. Whether meant as a joke or not, the experience cut deeply and reinforced her sense of being an outsider. The fixation on her looks would haunt her long after her talent became undeniable.

What no one could deny, however, was her voice.

In January 1963, she dropped out of college, hitchhiked to San Francisco, and began singing in coffeehouses. She lived hand to mouth, surviving on generosity and sheer determination. Record labels largely ignored her at first—she didn’t match the polished, conventional image they were seeking—but within the underground folk scene, her raw power was unmistakable.

San Francisco also exposed her to heavy drinking and drugs. Speed was legal and widely used, and when it became harder to find, she turned to heroin. Substance use became a way to numb the fear, pressure, and loneliness that followed her growing recognition.

By 1965, she was physically and emotionally exhausted. She returned to Texas dangerously underweight, entered therapy, re-enrolled in college, and even considered a conventional career. But music refused to let go.

When she was invited back to San Francisco to sing with Big Brother and the Holding Company, everything changed.

By the time the band performed at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1966, San Francisco had become the epicenter of a cultural revolution. Originally booked for a modest slot, Janis’s performance electrified the audience so completely that the band was immediately rescheduled for a prime evening appearance. Industry executives took notice, and a major record deal followed.

Overnight, Janis Joplin became a symbol of the counterculture. The woman once mocked for her looks was suddenly hailed as magnetic, fearless, and irresistibly powerful. She became the first female rock star to achieve true icon status, gracing the covers of Rolling Stone and Newsweek.

After releasing two albums with Big Brother, she pursued solo projects with the Kozmic Blues Band and later the Full Tilt Boogie Band. Her music left an indelible mark, producing hits like “Piece of My Heart,” “Cry Baby,” “Ball and Chain,” “Summertime,” and her posthumous No. 1 single “Me and Bobby McGee.” Her final recording, “Mercedes Benz,” remains haunting in its simplicity.

Despite her fame, Janis carried a deep need for approval—especially from her parents. Letters written home reveal a persistent desire to justify her choices and make them proud. Though worried about her drug use, her parents remained supportive, even inviting friends over to watch her perform on The Ed Sullivan Show.

She died on October 4, 1970, at just 27 years old, after using an unusually pure batch of heroin that claimed several lives that same weekend. She was cremated in Los Angeles, and her ashes were scattered over the Pacific Ocean.

Janis Joplin was never just a performer. She was the sound of longing, rebellion, vulnerability, and freedom all at once—a woman who turned pain into power and proved that beauty doesn’t follow rules.

Her voice still does what it always did: it tells the truth, no matter how raw it sounds.