The old airport body scanners were once widely criticized as “virtual strip searches,” a label that captured public unease more than technical nuance—but not without reason.

Anyone who has passed through airport security knows the uneasy pause that comes with stepping into a scanner, arms raised, instructions barked through glass. Today the discomfort is mostly psychological. In the early 2010s, however, it was far more literal. For a brief period, some passengers were unknowingly subjected to imaging technology that revealed far more than most people believed acceptable.

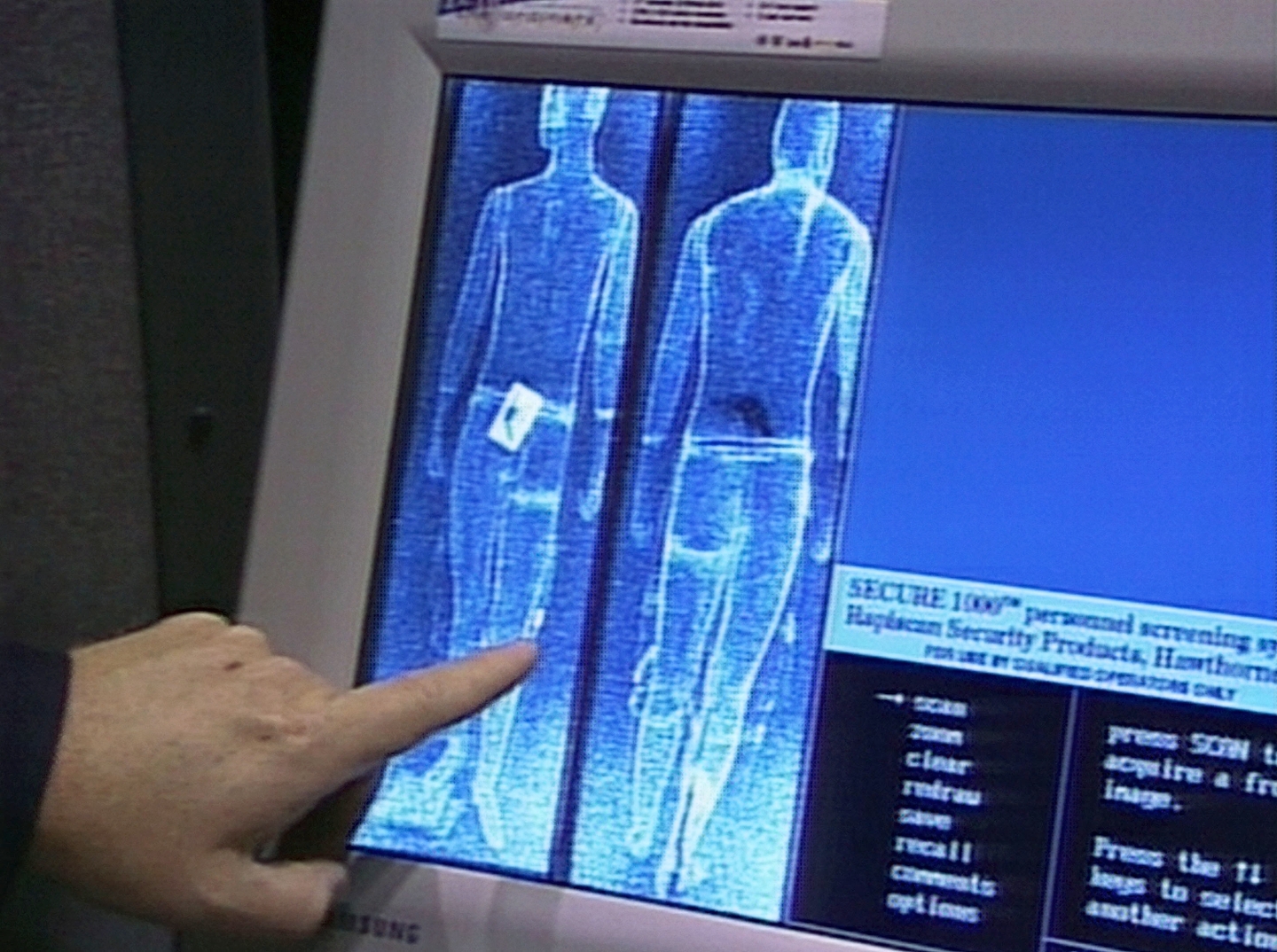

Following the 2009 Christmas Day bombing attempt, the Transportation Security Administration accelerated the deployment of advanced body scanners as part of a broader push to close security gaps. Among them were backscatter X-ray machines manufactured by Rapiscan. These scanners were rolled out across major U.S. airports with the stated aim of improving safety—but they quickly became a flashpoint.

The images produced by early backscatter scanners displayed detailed outlines of passengers’ bodies. While officials emphasized that the images were viewed by officers in separate rooms and not stored, many travelers and privacy advocates argued that the level of detail was excessive and invasive. Trust eroded quickly once the public learned what the technology actually revealed.

Critics dubbed the process a “virtual strip search,” not as a rhetorical flourish, but as an expression of a deeper concern: how much personal privacy should be surrendered in the name of security. Online reactions ranged from frustration to disbelief, with many questioning whether the scanners provided real protection or merely the appearance of control.

By the numbers, the program was significant. Each scanner reportedly cost around $180,000, and by the time concerns peaked, more than 170 units had been installed at dozens of airports nationwide. Yet the controversy proved decisive. In 2013, the TSA removed the backscatter scanners after they failed to comply with updated privacy requirements mandating the use of Automated Target Recognition software.

ATR technology replaced detailed body images with generic outlines, highlighting potential threats without displaying a person’s unique physical features. When Rapiscan could not adapt its machines to meet this standard, the scanners were withdrawn.

They were replaced by millimeter-wave scanners, which remain in use today. Unlike earlier systems, these scanners rely on abstract imaging and advanced sensors, flagging areas of concern without exposing anatomy.

As researcher and author Shawna Malvini Redden explained in an interview with Reader’s Digest, early versions of the technology were deployed without sufficient privacy protections. Today’s systems, by contrast, are designed to separate threat detection from personal exposure.

For many travelers, learning about the early scanners years later has been jarring. The episode serves as a reminder that technological capability often advances faster than ethical consensus—and that public oversight matters.

From a deeper lens, the story is not merely about scanners, but about boundaries. Security is essential, but so is restraint. When fear accelerates decision-making, safeguards must be strengthened rather than suspended. Progress, when it is genuine, learns from its overreach.

The machines are gone. The lesson remains: privacy, once compromised, is difficult to restore—and vigilance is required not only against threats, but against the quiet normalization of intrusion.