Scientists have revealed the three most dangerous tsunami zones in the United States—and the threat is far more real, and far closer, than most people think. The Pacific Northwest, East Coast, and Gulf Coast all sit in the crosshairs of potentially catastrophic waves triggered by underwater earthquakes, landslides, and rising sea levels. Millions of people live in the path of these looming disasters. And while tsunamis may feel like rare, distant events, they’re more like ticking time bombs waiting to be set off.

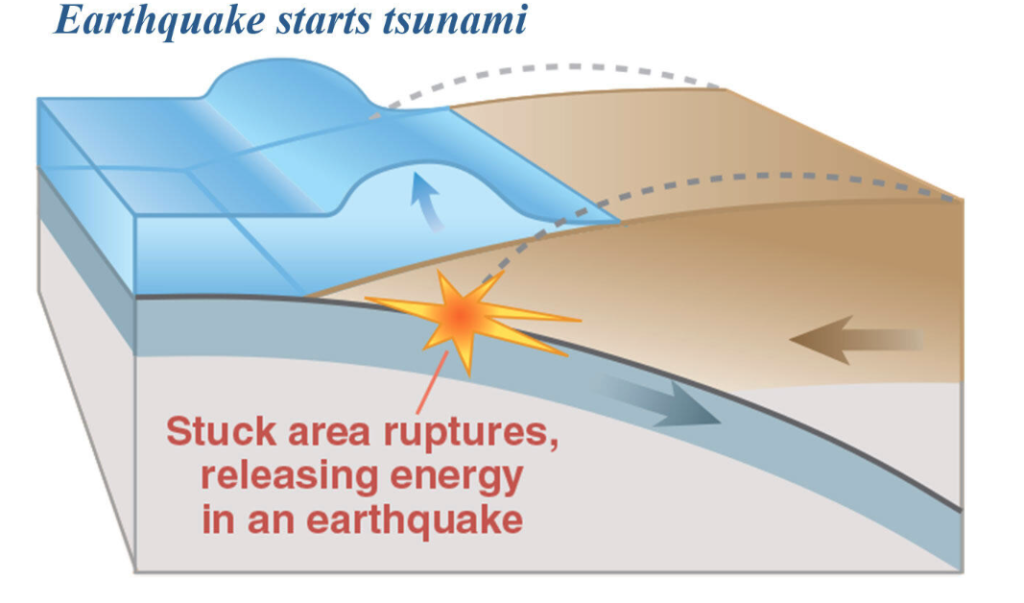

Tsunamis aren’t your typical beach waves. They don’t roll in gently or offer surfers a thrill. They’re generated when a massive shift happens under the sea—earthquakes, landslides, even volcanic eruptions. These waves tear across oceans at up to 500 miles per hour. In the deep sea, they appear subtle. But once they approach shallower waters, they rise dramatically and strike with brutal force. One key fact to remember: tsunamis are not tidal waves—they don’t come from tides, and they’re anything but routine.

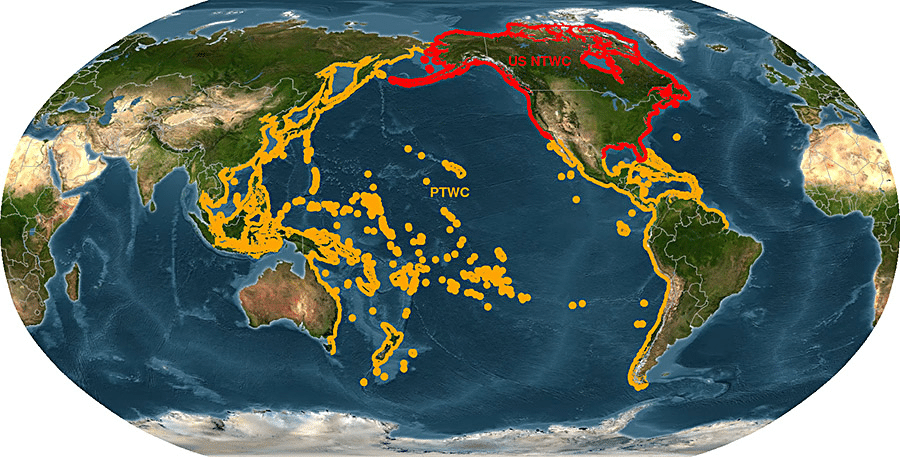

The Pacific Northwest holds the title of the most dangerous tsunami zone in the country. Washington, Oregon, and Northern California sit atop the Cascadia Subduction Zone—a 700-mile-long underwater fault line. The last time this fault ruptured was in 1700, creating a megaquake that sent a wave crashing across the entire Pacific to the shores of Japan. Scientists now estimate there’s a 10–14% chance of another magnitude 9.0+ quake within the next 50 years. If that happens, waves 30 to 100 feet tall could destroy coastal towns in minutes. Even worse, entire communities could sink as the ground suddenly drops several feet, worsening the flooding and leaving people trapped below sea level.

You don’t need to dig far to find proof of past devastation. Walk along the coastline and you might stumble upon “ghost forests”—stands of long-dead trees, their trunks bleached and bare. They’re eerie reminders of the 1700 event, when land dropped and seawater surged in, killing the trees instantly. Native oral traditions and Japanese tsunami records both describe massive waves wiping out entire villages. These natural disasters occur every 300 to 600 years. And if history holds, we’re overdue.

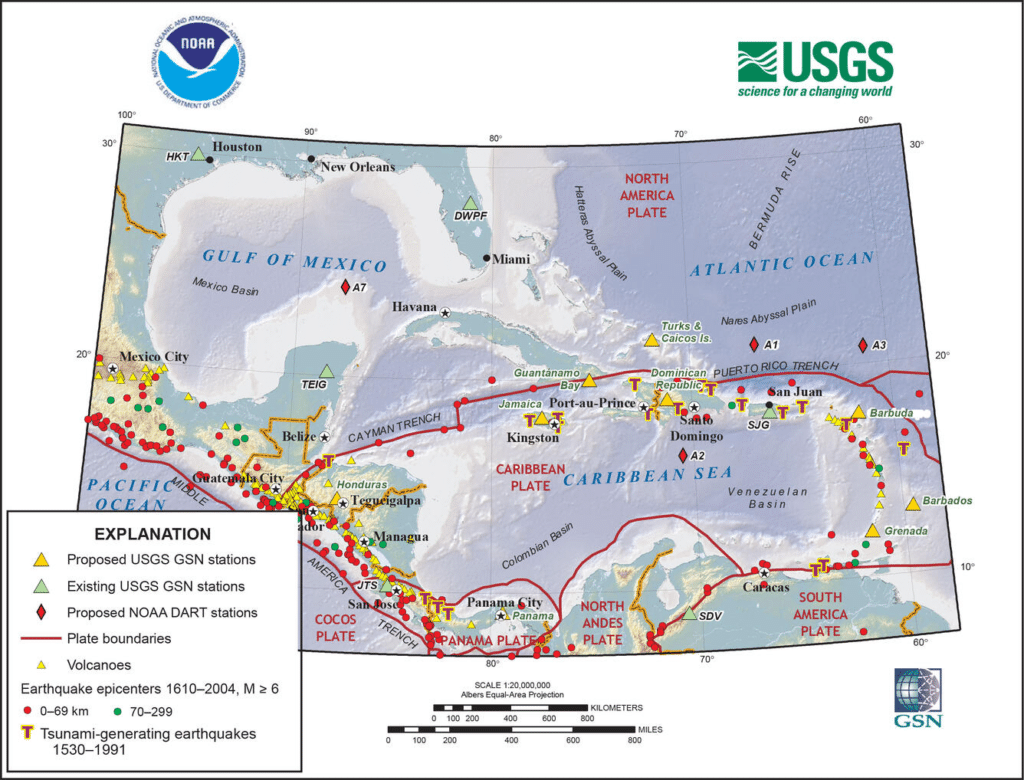

The East Coast, meanwhile, may feel far removed from Pacific threats—but that’s a dangerous illusion. The risk here is quieter but no less deadly. Underwater landslides along the continental shelf and distant quakes—like the massive 1755 Lisbon earthquake—have already proven that tsunami waves can reach the U.S. Atlantic shoreline. Of growing concern are the Caribbean fault systems, which stretch more than 2,000 miles. An earthquake there could send lethal waves toward the southeastern U.S., including Florida.

This isn’t theoretical. In 1918, a tsunami struck Puerto Rico, killing 40. In 1946, a far deadlier wave slammed the Dominican Republic, claiming over 1,600 lives. The region remains seismically active and capable of triggering tsunamis that could affect more than 35 million Americans.

Even the Gulf Coast, often dismissed as low risk, isn’t entirely safe. While the shallow waters and protective geography of Florida and Cuba offer some buffer, the threat persists. Historically, wave heights have peaked at around 3 feet, but that’s enough to cause damage and panic, especially during storms. Most of these waves are technically “seiches”—oscillations caused by atmospheric pressure or wind—but Caribbean-origin tsunamis remain the greatest concern.

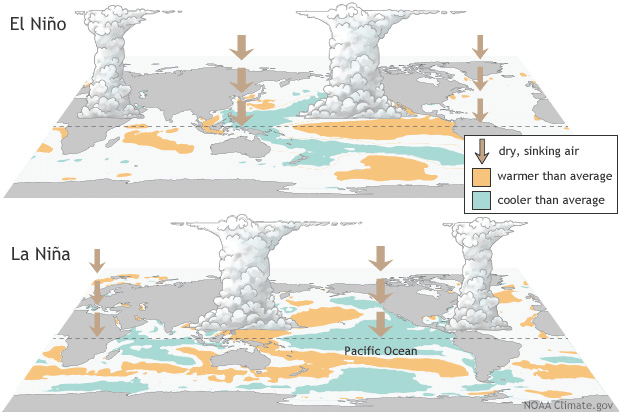

Then there’s the wildcard no one can ignore: climate change. Rising seas are already eroding coastlines and pushing high tides farther inland. Add a tsunami to the mix, and you get “compound flooding”—a devastating combo of higher water levels and sinking land that increases the reach and power of a wave. Studies show just 3 to 7 inches of sea level rise caused 70% more beach erosion during El Niño events. In a warming world, tsunamis become even more destructive.

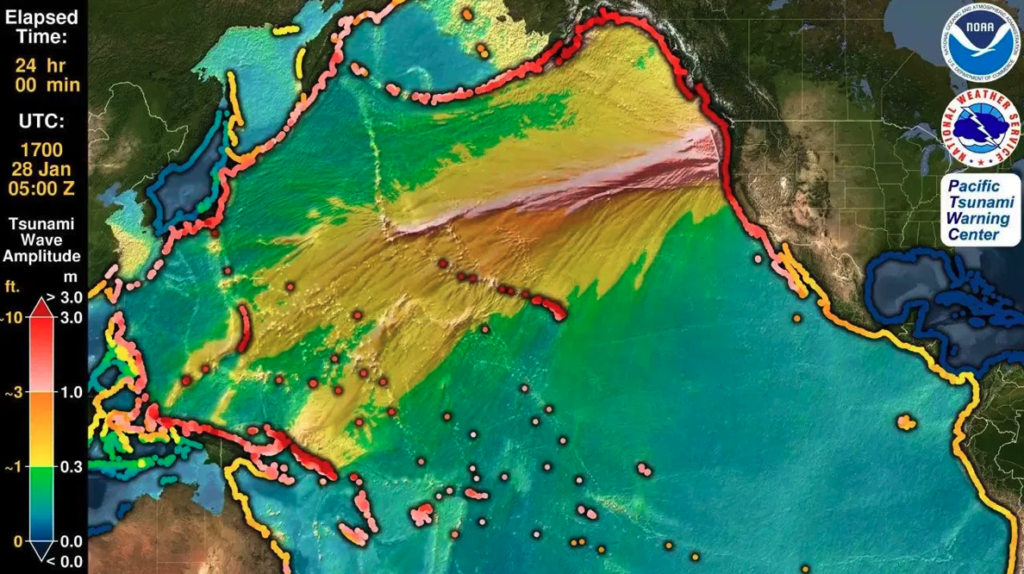

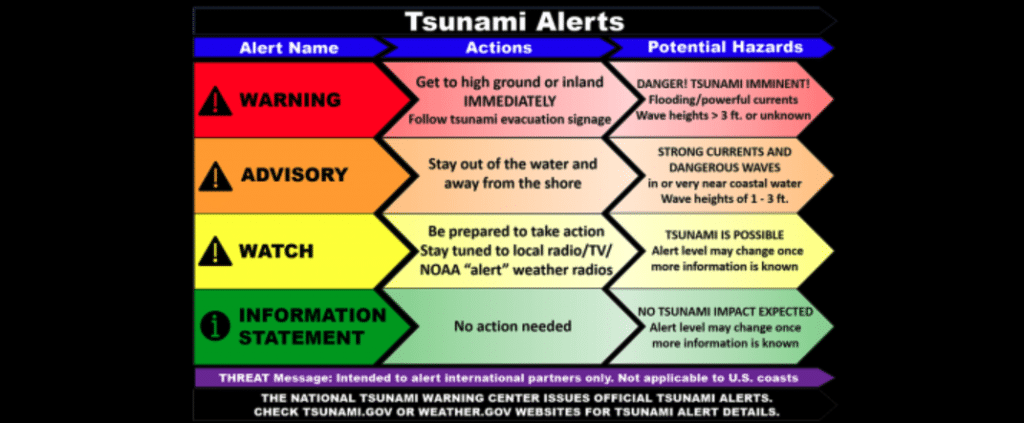

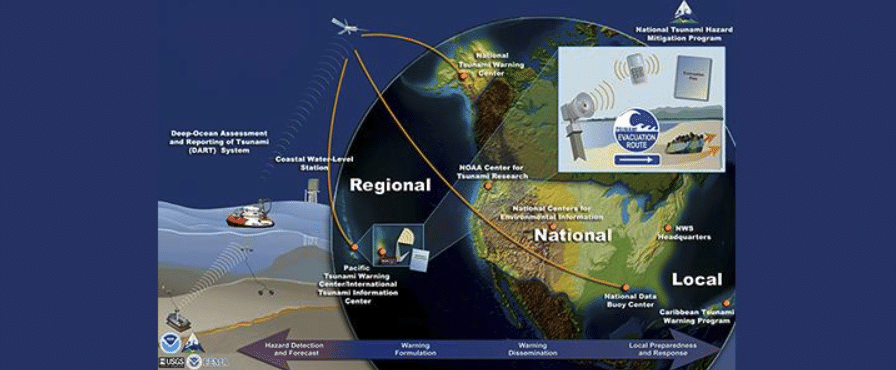

The U.S. does have sophisticated tsunami warning systems—including ocean buoys and coastal sensors—but they aren’t perfect. They work well for quakes that occur far away, giving people hours to prepare. But if an earthquake happens nearby, you might have just 15 to 20 minutes to escape. That’s not enough time to wait for sirens or alerts, especially if power is already out or cell towers are down. In those cases, your best warning system isn’t technology—it’s your own instincts.

Feel a strong earthquake near the coast? Don’t wait. Run to higher ground immediately. See the ocean pull away from the shore, exposing the sea floor? That’s nature screaming at you to move—now. Curiosity in those moments is deadly. Know your escape routes. Practice them. Pick a meeting point. Keep a go-bag with food, water, flashlight, radio, and first aid. Emergency preparedness isn’t overreacting—it’s surviving.

Scientists are working hard to understand these risks. They’re mapping underwater landslides, studying sediments to learn when past tsunamis struck, and building better monitoring equipment. They’re using satellites, submersible drones, and old-fashioned geology to fill in the gaps. But even with all their data, the next wave could come with no more than a rumble beneath your feet.

The Pacific Northwest is the most at risk. The East Coast is more vulnerable than most people realize. The Gulf Coast, though safer, is far from immune. Climate change is making all of it worse. Technology helps, but only personal readiness can truly save lives.

The question isn’t if another killer wave is coming—it’s when. Will you be ready when it hits?