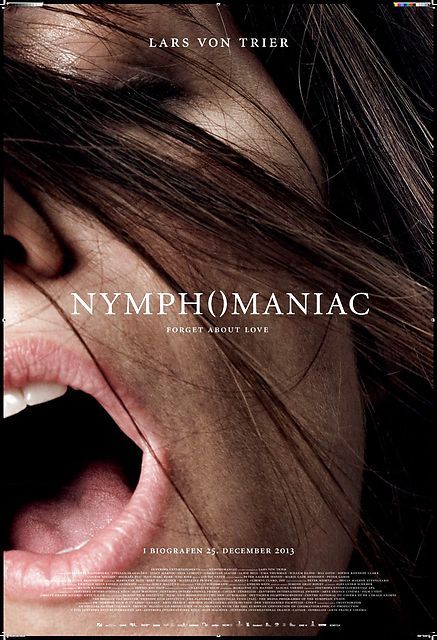

When Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac premiered in 2013, it didn’t simply arrive in cinemas—it detonated.

Marketed as a poetic and daring chronicle of one woman’s intimate life from childhood to age fifty, the film follows Joe, a self-described nymphomaniac, as she recounts her story after being found beaten in an alley. What unfolds is less a straightforward confession and more a layered, philosophical excavation of desire, shame, power, loneliness, and obsession.

Told in two volumes, the film stars Charlotte Gainsbourg as the older Joe and Stacy Martin as her younger self. Stellan Skarsgård plays the solitary man who listens to her account, responding with intellectual digressions that compare her experiences to mathematics, religion, fly-fishing, and music. Around them gathers a striking ensemble cast, including Shia LaBeouf, Christian Slater, Uma Thurman, Willem Dafoe, Mia Goth, and Jamie Bell.

The premise alone signaled controversy. But it was the execution that divided audiences.

Von Trier structures the film into eight chapters, each unfolding like a confession disguised as literature. Joe speaks bluntly about her experiences, framing her life as a relentless pursuit of sensation—sometimes playful, sometimes destructive. Yet beneath the explicit surface lies something colder and more analytical. The film asks unsettling questions: Is desire liberation? Is it addiction? Is it power? Or is it emptiness dressed as control?

What startled many viewers was not only the frankness of the subject matter but the realism of its portrayal. The production famously combined actors’ performances with digital compositing and body doubles to create scenes that felt unfiltered and confrontational. Producer Louise Vesth explained at Cannes that the actors performed non-explicit versions of scenes, which were later digitally blended with doubles in post-production. The result blurred the boundary between cinema and something more invasive.

That realism has prompted repeated viewer warnings online.

“If you’re planning to watch Nymphomaniac Pt. 1 & 2, watch it alone,” one social media user advised.

Others echoed similar sentiments, suggesting that the film’s intensity makes it unsuitable for casual or communal viewing. It is not background entertainment. It demands attention—and perhaps privacy.

Critics responded with equal intensity.

Volume I holds a 77% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, while Volume II sits lower at 59%. But numbers hardly capture the emotional range of the reviews. Some praised its ambition and refusal to soften uncomfortable themes.

“With its wildly absurdist obscenities, fearlessly bold performances and wilfully indulgent lack of structure, Nymphomaniac provokes the now familiar symphony of sighs, gasps and laughs,” one critic wrote.

Another described it as “outrageous, inspired, infuriating, puerile, confounding, cruel, beautiful, funny”—a film impossible to reduce to a simple verdict.

Yet others found it emotionally distant or overly indulgent. Some argued it reflects a distinctly male lens examining female desire, questioning whether it truly represents a woman’s interior life or merely dissects it.

And that tension may be the point.

Von Trier has long built his reputation on discomfort. Nymphomaniac does not aim for universal approval. It invites debate, confrontation, and introspection. For some viewers, it feels like a fearless exploration of sexuality and guilt. For others, it feels like provocation for its own sake.

A decade later, the film continues to circulate—now streaming on platforms like Netflix and Kanopy in the United States—where new audiences discover it without the festival buzz that first surrounded it.

But the warnings remain.

Nymphomaniac is not casual viewing. It is deliberate, explicit in theme, and emotionally unfiltered. Whether seen as art, experiment, or excess, it is undeniably one of the most talked-about films of the 2010s—a cinematic confession that refuses to whisper.