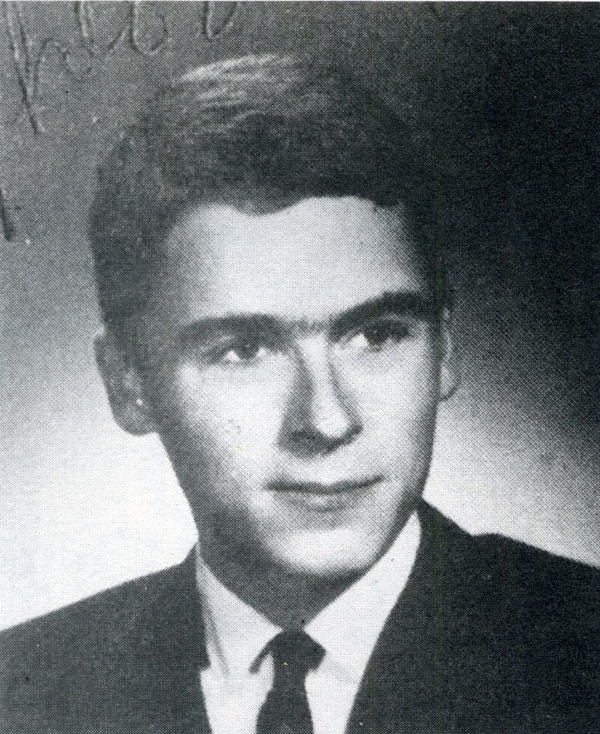

He appeared, by all outward measures, to be an ordinary boy growing up in a quiet American town. Shy and soft-spoken, he delivered newspapers, participated in the Boy Scouts, and blended easily into his surroundings. Nothing about the child in that early photograph suggested the future that awaited him—or the name that would later become synonymous with terror.

Yet that boy would grow up to be Ted Bundy, one of the most notorious criminals in modern history.

A life built on deception

Born in 1946 in Burlington, Vermont, Bundy’s entry into the world was marked by secrecy and instability. His father was never identified, and rumors later circulated that he may have been conceived through incest—claims that have never been definitively proven but nonetheless haunted discussions of his past.

He spent his first months in a home for unwed mothers before being sent to live with his maternal grandparents in Philadelphia. For years, he was raised to believe that his mother, Louise, was actually his older sister. His grandparents were presented as his parents, and the truth about his origins was carefully concealed.

Bundy would later suggest that he had suspected the truth from a young age. “I just grew up knowing that she was really my mother,” he said, reflecting on how Louise was always the one who cared for him most closely. Accounts differ on when he learned the truth definitively—some suggest he discovered his birth certificate as a teenager, others that a cousin revealed it to him earlier—but the revelation left a lasting psychological imprint.

Early warning signs

By many accounts, his childhood appeared relatively stable. Neighbors described the family as respectable and pleasant. He played with friends, joined youth organizations, and was generally well-liked. Yet beneath the surface, unsettling behavior occasionally emerged.

One family member later recalled waking to find Bundy, still a child, standing by her bed with knives arranged nearby—an incident that alarmed her but was never formally addressed. Retrospectively, such moments would be scrutinized as possible early indicators of deeper disturbance.

At school, he struggled socially. A speech impediment made him a target for teasing, and repeated failures to make athletic teams bruised his self-esteem. By adolescence, he had become increasingly isolated, going on only one date throughout high school and retreating inward as feelings of inadequacy grew.

Identity, resentment, and obsession

Tensions intensified at home when Louise began a relationship with a new man who became a stepfather figure. Bundy reportedly resented him, particularly because he could not provide the material comforts Bundy craved. He developed an intense fixation on status, appearance, and wealth—fantasizing about a life far removed from his working-class reality.

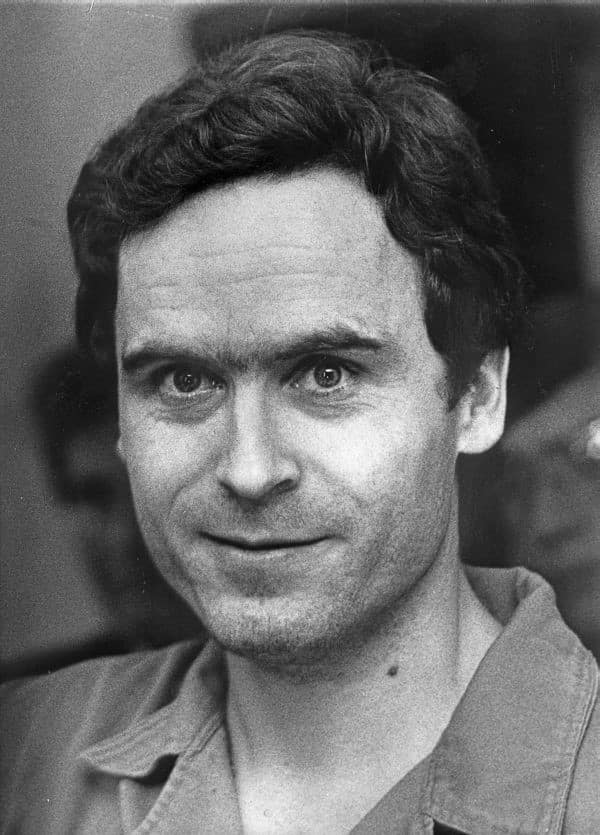

Outwardly, Bundy appeared to move forward. He attended college, presented himself as intelligent and ambitious, and even volunteered on a suicide prevention hotline—an irony that would later horrify the public. Privately, however, he nurtured violent fantasies that would soon manifest in real-world brutality.

A calculated predator

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Bundy embarked on a killing spree that spanned multiple states. His methods were chillingly methodical. He often posed as an authority figure or feigned injury to gain sympathy, luring young women with charm and apparent vulnerability.

Once he gained their trust, he struck.

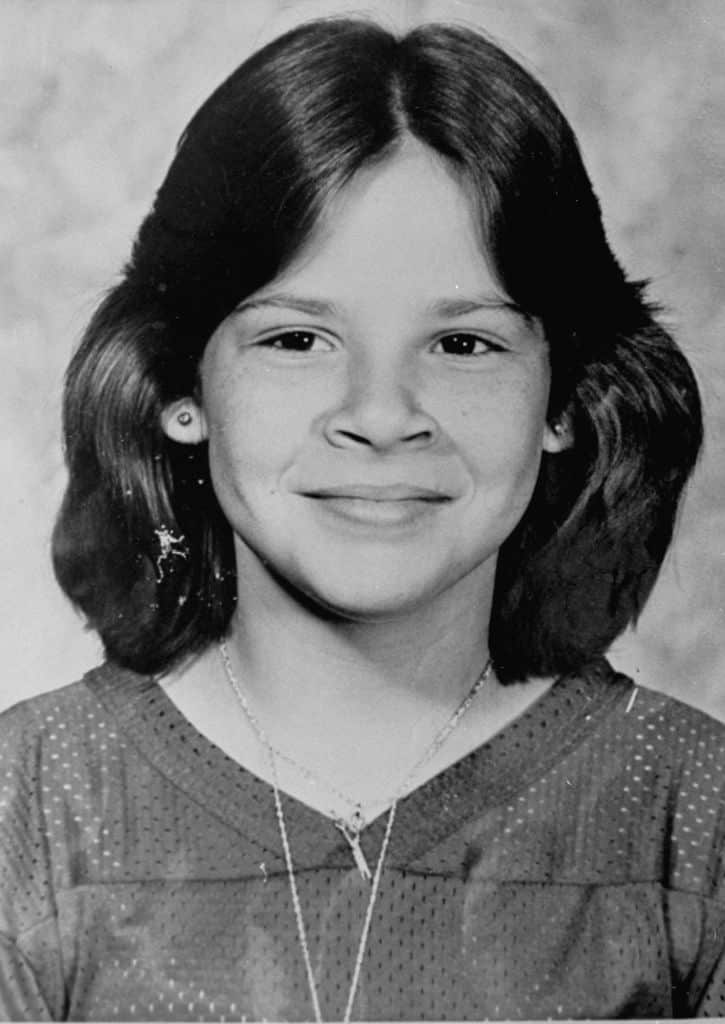

His first confirmed murder occurred in 1974, though investigators believe his crimes may have begun years earlier. Among the suspected early victims was eight-year-old Ann Marie Burr, who disappeared from her Tacoma home in 1961. Bundy never formally confessed to her murder, but investigators long considered him a prime suspect.

Over time, survivors came forward with eerily similar accounts: deception, sudden violence, restraint, and disappearance. His victims—at least 30 by his own later admission—were predominantly young white women, many of them college students.

Capture and conviction

Bundy’s spree began to unravel in August 1975 when a police officer stopped him for speeding and discovered suspicious items in his vehicle, including a ski mask and crowbar. The name on his license—Theodore Robert Bundy—would soon dominate national headlines.

Though he was ultimately convicted of only three murders, Bundy later confessed to killing dozens of women across seven states between 1974 and 1978. Many experts believe the true number is significantly higher.

In Florida, he was sentenced to death in two separate trials. As appeals failed and execution neared, public reaction was intense. Some viewed his impending death as justice long overdue; others criticized the spectacle that formed around it.

The final moments

Bundy was executed in the electric chair at Florida State Prison on January 24, 1989. He declined a special last meal and offered only brief final words: “I’d like you to give my love to my family and friends.”

Outside the prison, crowds gathered—some cheering, others holding signs bearing the names of victims. Fireworks were set off as news of his death spread, underscoring the depth of emotion his crimes had stirred.

Former FBI profiler William Hagmaier later noted that Bundy spoke of his murders in terms of control rather than emotion, suggesting that even at the end, he remained detached from the devastation he caused.

A disturbing legacy

The story of Ted Bundy continues to provoke difficult questions about nature, nurture, and the hidden capacity for violence. He did not look like a monster. He did not begin as one. His life stands as a chilling reminder that evil does not always announce itself—and that the most ordinary appearances can sometimes conceal the darkest realities.